Some jasper made at Adams’ Greengates Pottery in Tunstall was equal to, if not superior to, jasper made by Wedgwood at Etruria

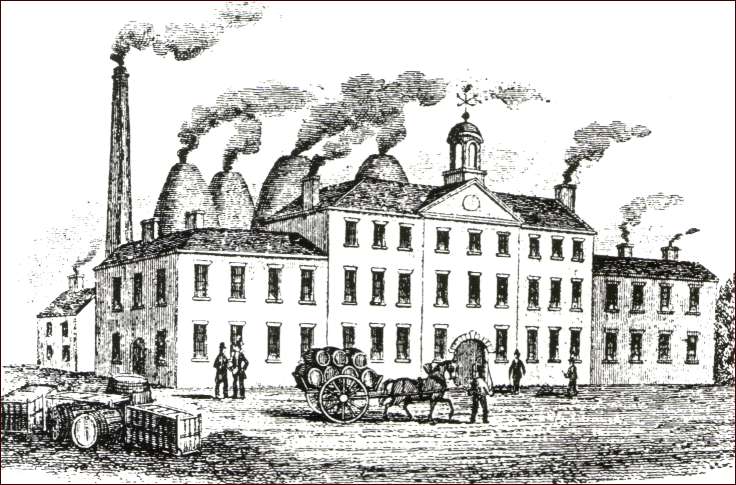

William Adams’ Greengates Pottery in Tunstall.

During the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution changed the face of Britain, making it the ‘workshop of the world’.

Earthenware factories were built in Tunstall, a township that included Sandyford, Newfield and Furlong. At the end of the 18th century, there were seven factories making pottery. Small coal and ironstone mines were scattered throughout the district. Blue bricks and tiles were made in the Chatterley Valley.

As early as 1735, William Simpson was making earthenware in the township. By 1750, Enoch Booth had a factory near a field called Stony Croft. The factory made cream coloured ware glazed with a mixture of lead ore and ground flint.

In 1763, Admiral Smith Child built Newfield Pottery, where he produced earthenware. By the 1780s, two brothers, Samuel and Thomas Cartlich, were making pottery and mining coal at Sandyford. There were brick kilns, coal mines, a flint mill and a crate maker’s workshop at Furlong.

During the 1740s, George Booth and his son Thomas leased a pottery factory. on an estate called Will Flats, next to Furlong Lane. In 1779, Burslem pottery manufacturer William Adams rented the factory and part of the estate.

On 1 March 1784, William purchased the factory and the land he had been renting. He changed the estate’s name from Will Flats to Greengates and demolished the old factory.

William built Greengates Pottery (shown above), where he made high-quality stoneware and jasper ornaments for the luxury market. He employed Swiss modeller Joseph Mongolot. Joseph helped him create models for moulds to produce the bas-reliefs for jasper and stoneware.

Pottery produced by William was sold to wealthy customers. Some purchased ware from his showrooms in Fleet Street, London. Others visited the Greengates factory’s showrooms where they bought tea sets, dinner services, jasper, and stoneware ornaments.

In his book, Marks and Monograms on Pottery and Porcelain, William Chaffer mentioned the quality of Adams’ jasper. He said some of it was “equal to, if not superior to” jasper made at Etruria by Wedgwood.

Revised: July 2025