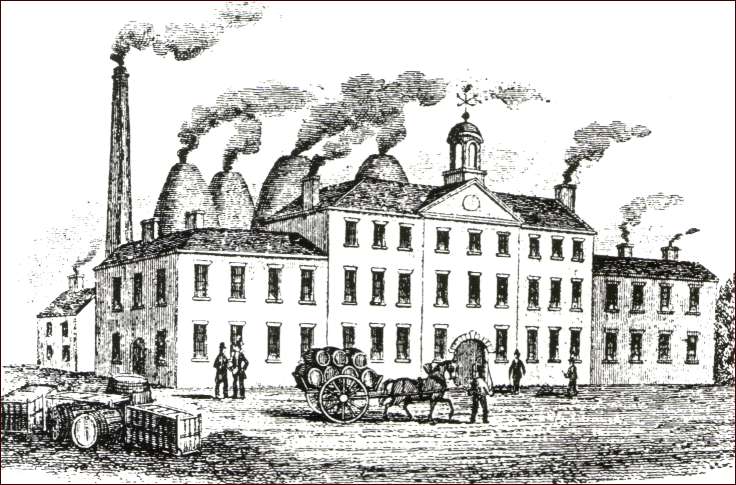

The sketch above shows William Adams’ Greengates Pottery in Tunstall. The factory built between 1779 and 1781 was one of the largest in the Potteries. It manufactured tableware, stoneware and jasper ornaments for the luxury market. William Chaffer, the author of ‘Marks and Monograms on Pottery and Porcelain’, said some of the jasper made at Greengates was ‘equal to, if not superior’ to that produced by Josiah Wedgwood at Etruria.

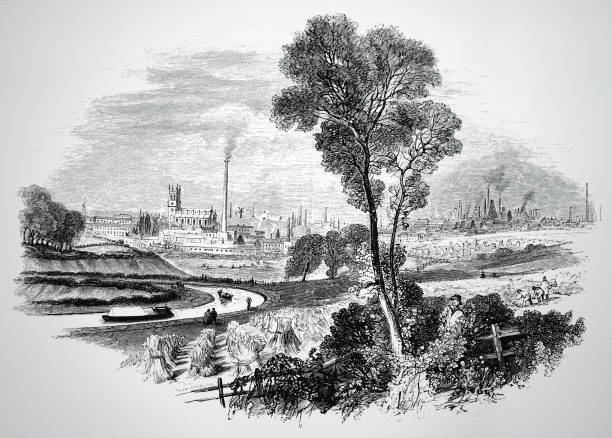

A Description of the Country From Thirty to Forty Miles Round Manchester, a book published in 1795, was compiled by Dr John Aikin. The book tells us about Newcastle-under-Lyme and North Staffordshire’s pottery towns and villages in the 1790s.

This edited extract from the book describes Tunstall as it was in the 1790s.

Tunstall is the pleasantest village in the Potteries. It stands on high ground, commanding extensive views of the surrounding countryside. Pottery manufacturers in the village produce good-quality ware and do considerable business. There was a church here, and human bones have been dug up. But such is the effect of time that no trace of either the church or the bones remains today. A small chapel has recently been built here. There is a considerable number of brick and tile works. They use local clay to make blue bricks, which look as well on the roofs of houses as moderate slate. Tunstall is four miles from Newcastle-under-Lyme and nine miles from Congleton. The turnpike road from Lawton to Newcastle-under-Lyme runs through Tunstall, where the turnpike road to Bosley in Cheshire begins [near the Wheatsheaf Inn].