In the 19th century, Stallington Hall was the home of Sir Smith Child. He was born at Newfield Hall in Tunstall. During his long life, Smith Child gave financial support to the North Staffordshire Infirmary and charities in Tunstall. He became North Staffordshire’s most generous philanthropist. The clock tower in Tunstall’s Tower Square was erected to make sure that his generosity would not be forgotten. Smith Child died at Stallington Hall on 27 March 1896. He was buried in Fulford churchyard.

Our History

Turn the clock back a 100 years

Become a time traveller. Go to Longton Park’s Centenary Carnival on 10th August and turn the clock back to 1925.

You will see what the park was like when Stoke-on-Trent was granted city status. There will be fun for you and your family. You can listen to music from the roaring twenties or play hopscotch and other children’s games. Take your children to a funfair. Watch a Punch and Judy show and see a collection of vintage vehicles. It will be a great day out for all the family.

The event takes place from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Admission is free.

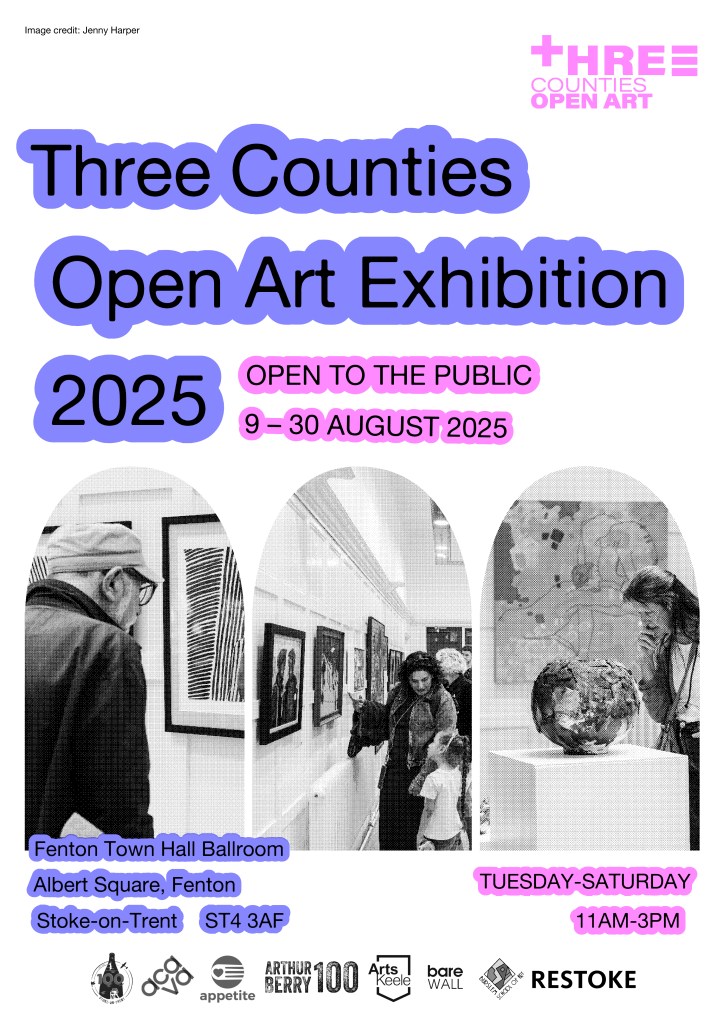

The Three Counties Open Art Exhibition

This year’s Three Counties Open Art Exhibition is being held in the ballroom at Fenton Town Hall. The exhibition runs from Saturday, August 9th, until Saturday, August 30th. It will be open on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays.

Artists from Staffordshire, Shropshire, and Cheshire are exhibiting their work, which includes paintings, drawings, sculptures, and moving images.

The cafe in the town hall will be open for refreshments and light bites.

More details can be obtained from open.art@keele.ac.uk

The end of a busy week

It’s late Friday afternoon. We have come to the end of a busy week. New apps have been installed on the computer, and specialist scanners have been acquired for the office. A major new research project starts on Monday. It will look at life in the Middle Ages, with special reference to the administration of justice. Have a relaxing and enjoyable weekend. Stay safe.

Child’s Tea Set made in Tunstall by Plex Street Pottery

This delightful child’s tea service was made in the 1950s at the Staffordshire Tea Set Company’s Plex Street Pottery in Tunstall. We discovered this factory while researching the history of education in the Potteries.

High Street Tunstall (c.1900)

This postcard shows Tunstall High Street at the end of the 19th century. Notice the tram line and the tram in the middle of the road. In the distance, you can see Lawton’s Tile Works at the Haymarket, where Roundwell Street joins High Street.

Staffordshire History Centre – A Volunteer’s View

I am a new volunteer. I have loved local history since I was a child. This place is my idea of a haven. From Lotus Shoes and Evode to William Palmer in the main exhibition space, through to the beautiful rooms of the William Salt Library, our collection spans many centuries, highlighting how Staffordshire has contributed to the UK and the wider world over and over again.

John Nash Peake (1837-1905)

John Nash Peake, after whom Nash Peake Street is named, was one of Tunstall’s most flamboyant characters. Born in Tunstall on 13 April 1837, he was the son of Thomas Peake.

Thomas owned Tunstall Tileries, in Watergate Street. He was the town’s Chief Bailiff (Chief Constable) and Chairman of the Board of Health from 1858 to 1861.

John, whose Christian names were John and Nash, was educated at the North London Collegiate School. At school, he showed considerable artistic ability. When he left school, John became a student at the Royal Academy, where he studied under Millais, one of England’s leading artists.

One of John’s paintings, Alpine Monks Restoring a Traveller, was exhibited at Burlington House when he was 18 years old. A year later, he showed another painting, The Last Hours of the Condemned, which portrayed a soldier awaiting execution.

Although he could have stayed in London and become a professional artist, John returned to Tunstall in the 1850s. He joined his father’s company, which made bricks, tiles, water pipes and ornamental garden pottery. John managed the firm after Thomas’s death in 1881. Under his management, the works doubled in size. It became one of the largest tileries in the world. There were 35 ovens producing more than 250,000 tiles a week.

John had a strong personality. He was a man with a keen intellect and a commanding presence, who was eloquent, versatile and persevering.

A devout Christian, John was an evangelist and a member of the Church of England. He opposed the Oxford Movement’s attack on the Reformation and its plan to make the Pope head of the Church of England.

His views on the activities of the Oxford Movement were shared by Sir Smith Child and Tunstall’s leading Methodists.

John spoke out against the movement’s growing influence and the introduction of Roman Catholic dogma and rites into Potteries’ churches. The Wesleyan Methodists invited him to lay one of King Street Methodist Church’s* four foundation stones.

The stones were laid on 20 October 1873. During the ceremony, John said he was sure that the Wesleyan Methodist Church would defend the Protestant faith. He was grieved to see the Church of England abandoning its traditions and embracing the doctrines of Roman Catholicism. John advised the Wesleyans to adhere to their faith and not allow anyone to interfere with it. He told them that the doctrines being introduced into the established church would destroy the Reformation.

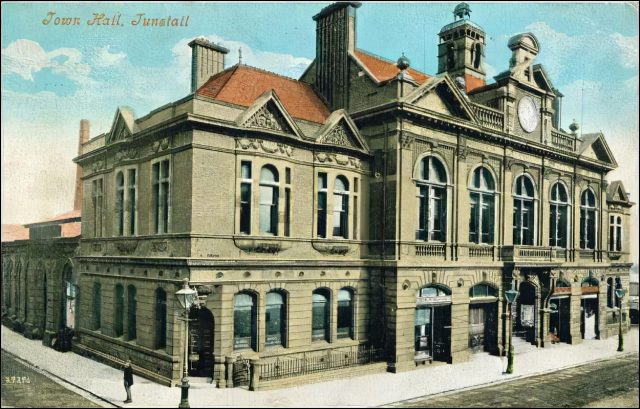

John was a member of the Liberal Party. In 1869, he became a member of Tunstall’s Board of Health. His energy and determination led to the creation of the town’s Victorian civic centre. This centre included a new town hall and a public library as well as a school of art and science, a museum, a fire station, public baths, a drill hall and a recreation ground.

Despite his busy commercial and political life, John retained his interest in art. He painted portraits of Queen Victoria, Lord Roberts, and his father (Thomas Peake). He also painted Sir Smith Child and civic leaders, including Alfred Meakin, George Wilks, Henry Smallman, and Thomas Booth. These portraits hung in the town hall. A self-portrait which he painted was hung in the museum. Other examples of his work displayed there included Bosley Reservoir and Cloud End, The Fishing Fleet at Tenby, Menai Suspension Bridge, The Isle of Arran and The Matterhorn.

He designed the Free Library sign that hangs outside the Jubilee Building and Victoria Park’s main gates, which were erected in memory of his father.

On 15 October 1903, John gave Tunstall a mahogany cabinet with drawers to store the town’s records. One of his portraits of Queen Victoria is incorporated into the cabinet. The cabinet remains in the council chamber of the former town hall. Its doors open to reveal a list of the main events in the town’s history. There are also photographs of the chief bailiffs (Chief Constables), clerks, and surveyors from 1855 to 1909.

A bronze portrait bust of John was unveiled in the council chamber. He was given an illuminated address to thank him for his services to the town.

John, who was 66 years old, said: “I know well that day by day, I come nearer to a time when I shall be forever absent from the council chamber and the streets. Think, then, what it means to me this surprising tribute of yours that I shall not be forgotten: that I shall be with you, dwelling among my own people in imperishable bronze.”

He died three years later on 29 April 1905. The bronze bust disappeared many years ago. So far, all attempts to trace it have failed.

*King Street is now Madison Street. The church was demolished in the 1970s.

Note: John Nash Peake (1837-1905) is one of a series of articles Betty Martin wrote before she died in 2023. More articles from this series will be posted periodically.

18th Century potters left North Staffordshire to work in Liverpool

My story begins with a journey from Burslem in Staffordshire to Toxteth in Liverpool in November 1796.

To read the post, press the title A Herculaneum Potter (above).

Jane Austen Writes About Wedgwood Ware

In her letters Jane writes of visiting the Wedgwood showrooms in London and in one gleeful missive to her sister Cassandra in June 1811, she writes ‘I had the pleasure of receiving, unpacking, and approving our Wedgwood ware’ and anticipates the arrival of a new Wedgwood breakfast set for their mother, ‘I hope it will come by the waggon to-morrow; it is certainly what we want, and I long to know what it is like’.