A portrait of Sir Smith Child painted by John Nash Peake.

During the 19th century, Sir Smith Child was the most generous philanthropist in North Staffordshire. He used his vast wealth to support hospitals, build schools and churches, fight poverty and help handicapped children.

Although many historians think that his family name was Smith Child, it wasn’t. Smith was his Christian name and Smith was his surname. Smith Child was born at Newfield Hall, Tunstall, on 5 March 1808. His grandfather was Admiral Smith Child, who was a partner in Child & Clive. The firm owned Newfield Pottery and Clanway Colliery, where it mined coal and ironstone.

Smith’s parents were John George and Elizabeth Child, née Parsons. When his father died in 1811, he became heir to the Newfield estate and other estates owned by his grandfather.

Smith was educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge.

On 28 January 1835, he married Sarah Hill, an heiress, at Fulford Church. The couple had three children – two boys and a girl. The family lived at Newfield Hall until 1841, when they moved to Rownall Hall, Wetley. Sarah’s father, Richard Clarke Hill, who owned Stallington Hall, died in 1853, and the Childs went to live there.

Smith took a keen interest in politics. He was a Conservative. In 1851, he became the Member of Parliament for North Staffordshire and held the seat until 1859.

In 1868, Smith was made a baronet.

He stood for Parliament again. He won the election and was returned to Westminster as the Member for West Staffordshire. A seat he held until 1874, when he retired from politics.

Smith was a philanthropist who took a keen interest in the welfare of disadvantaged individuals. He used his wealth to support local charities that were helping those in need.

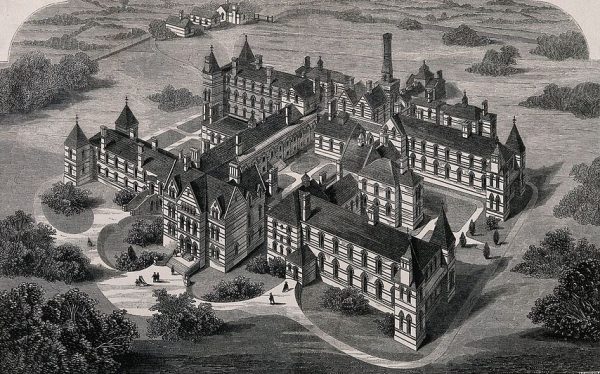

He provided financial assistance to the North Staffordshire Infirmary at Etruria and made an annual donation to its general fund. Smith was a member of the hospital’s management committee and served as its president on three occasions. As well as making an annual donation, he contributed to the infirmary’s special funds. The management committee decided to close the infirmary at Etruria and build a new one at Hartshill. It launched a public appeal to raise money to finance the project. A building fund was created, and Smith contributed £1,500. When the Victoria Wards were being erected, he gave £250 towards the cost.

After one of his sons died, Smith built and endowed the Smith Hill Child Memorial Hospital. The hospital, erected in the grounds of the infirmary, was designed to care for patients who were incurable. The infirmary did not have the resources to care for incurable patients, and the project was abandoned. The building was used as a nurses’ home until 1877, when it was converted into a children’s hospital.

In 1875, Smith founded a charity that sent patients who were convalescing to convalescent homes. He endowed the charity with £6,500. The money was invested in securities. The income from these securities was used to send hundreds of men, women and children to seaside convalescent homes.

Smith realised that the pottery industry’s future depended on vocational training.

He was one of the founders of the Wedgwood Institute and organised competitions that awarded prizes to industrial designers. To encourage sales representatives to study foreign languages, he gave prizes to those learning to speak French, German or Spanish.

Although he left Newfield Hall in 1841, Smith retained an interest in Tunstall and its citizens’ welfare. He always referred to people living there as his friends and neighbours.

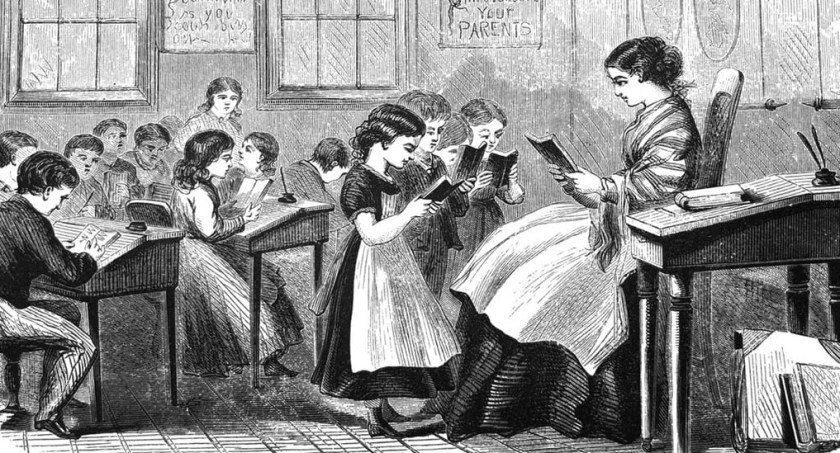

His first gift to Tunstall was £100, which was given to help finance the construction of Christ Church. He gave £50 when the church appealed for money to build a National School. The appeal was successful, and the school was built in King Street (Madison Street). When St. Mary’s Church launched an appeal to raise money to build a school, he gave £100.

Smith built the church schools in Goldenhill and created a charity to support all church schools in Tunstall and Goldenhill. He helped finance the construction of St. John’s Church in Goldenhill and endowed it with £1,000.

During the 1880s, he made donations to help regenerate Christ Church and St. Mary’s Church. In 1884, he established a workingman’s temperance club at Calver House in Well Street (Roundwell Street).

Six years later, in 1890, he founded the Tunstall Nursing Association. The association was a charity. It employed trained community nurses, who provided free medical care to patients being treated at home.

Tunstall publicly recognised Smith’s generosity in 1893. The clock tower in Market Square (Tower Square) was erected to make sure that he would never be forgotten.

Smith was to ill to attend the tower’s unveiling ceremony. His health continued to decline. He died three years later and was buried in Fulford churchyard

If you and your family worshipped at St. Mary’s or you were at pupil at the school, please use Comments to share your memories with us.

Sir Smith Child (1808-1896) was written by Betty Martin before she died in 2023. More articles she wrote will be posted periodically.