A Description of the Country From Thirty to Forty Miles Round Manchester, a book published in 1795, was compiled by Dr John Aikin. The book tells us about Newcastle-under-Lyme and North Staffordshire’s pottery towns and villages in the 1790s.

This edited extract from the book describes Longport in the 1790s.

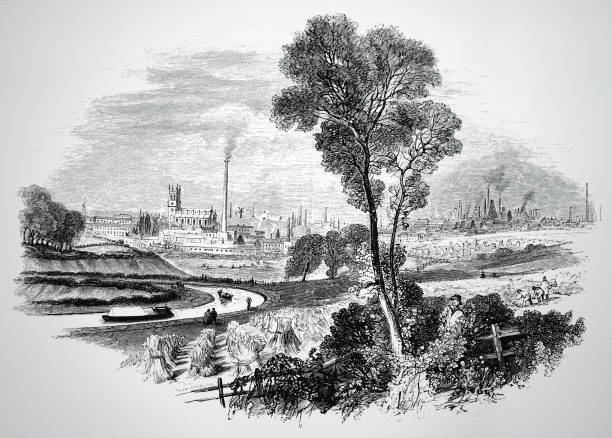

Longport is situated in a valley between Burslem and Newcastle. There are some good buildings in it and several large pottery factories. Because it is in a valley, there are times when the smoke from bottle ovens and kilns hangs over Longport, making the air disagreeable, if not unwholesome.

The Trent & Mersey Canal passes through Longport, where there is a public canal wharf. Before the canal was constructed, Longport was called Longbridge Hays because there was a kind of bridge that ran parallel for a hundred yards with the Fowlea Brook. The bridge was dismantled when the canal was cut.

The number of buildings increased rapidly when the canal was completed, and the village’s name was changed from Longbridge Hays to Longport.