Not far from Leek, the Cheddleton Asylum, later called St Edward’s Hospital, was the third County Asylum to be built in Staffordshire. This vast institution, initially designed to accommodate 618 patients in 16 wards, was intended to relieve chronic overcrowding at the Stafford and Burntwood Asylums. The site at Bank Farm, Cheddleton, near Leek, was decided upon in preference to the original proposal of land at Bramshall Park Farm, Uttoxeter, because it was on elevated land; a criteria considered essential to provide a healthy environment for the patients.

Month: Dec 2023

David and Lee Need Your Help

Before she died in 2023, North Staffordshire Heritage’s historical geographer, Betty Martin, planned to publish her extensive original research into Stoke-on-Trent’s history and architectural heritage.

Betty went to Brownhills High School and Tunstall always had a special place in her heart. A not-for-profit foundation is being set up to publish a series of books based on her research. The first books are about Tunstall. They are being written by Betty’s husband, David, and Lee Wanger.

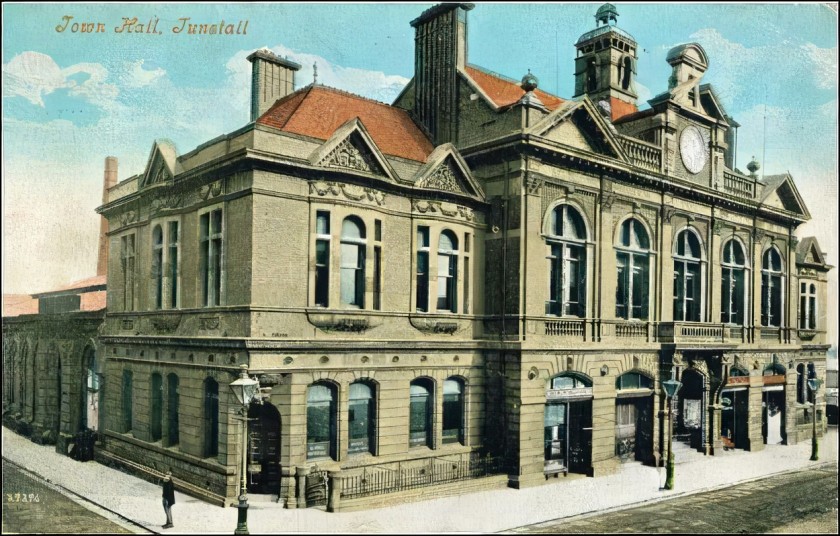

David and Lee are working on the first book, The History of Tunstall Town Hall and Market. Other books in the series include The History of the Jubilee Buildings and The Life of Sir Smith Child.

Senior citizens remember the town hall and market as they were before they closed for regeneration in the 1990s. They can recall social activities they went to in the town hall and going shopping in the market. Amateur photographers and students from Stoke-on-Trent College and Staffordshire University photographed the market and the town hall before they were regenerated.

David and Lee need your help to trace these photographs.

If you have photographs of the town hall or market please email davidmartin227@outlook.comm

The Mystery of Simeon Shaw

Simeon Ackroyd Shaw was born in Salford on April 17th, 1785. He became the Potteries’ leading intellectual in the first half of the 19th century.

Simeon came to North Staffordshire, where he worked as a printer and compositor for the Potteries Gazette and Newcastle-under-Lyme Advertiser.

In 1985, Keele University’s Department of Adult Education published People of the Potteries. The book says that by 1818, Simeon was “running an academy for young gentlemen in Northwood, Hanley”. According to People of the Potteries, in 1822, Simeon owned a commercial academy in Piccadilly, Hanley. By 1834, he had a large academy in the town’s Market Place.

When he was writing By-gone Tunstall (Published in 1913), William J. Harper was given notes called Tunstall Reminiscences written by Simeon’s grandson, Mr W. S. Shaw. In these reminiscences, Mr Shaw says his grandfather lived in Piccadilly Street, Tunstall. He had one of North Staffordshire’s largest and most influential academies in the Market Place (Tower Square).

White’s Directory of Staffordshire, published in 1834, shows that Simeon owned an academy in Market Place, Tunstall. Official records prove that he lived in Piccadilly Street, which ran from Market Place to Sneyd Street (Ladywell Road).

Simeon was still living in Piccadilly Street in 1851. He died on April 8th, 1859 and was buried in Bethesda churchyard Hanley.

Stagecoaches and Coaching Inns

When they left the Sneyd Arms in Tunstall, stagecoaches going to London followed the Old Lane through the Potteries, stopping at coaching inns in Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton.

During the 1830s, two firms, the Red Rover Company and the Royal Express Company, ran mainline stagecoaches between London and Liverpool.

Between Warrington and the Potteries, the coaches were driven along the Old Lane (the A50) that linked London and the East Midlands with Merseyside and the Northwest. These coaches stopped at the Sneyd Arms in Tunstall to pick up passengers. When they left the Sneyd Arms, the coaches followed the Old Lane through the Potteries, stopping at coaching inns in Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton.

On leaving Longton, coaches owned by the Royal Express Company left the Old Lane and went to London via Stone, Rugeley, Lichfield, Birmingham and Warwick. Coaches owned by the Red Rover Company followed the Old Lane to Hockcliffe in Bedfordshire, where it joined the London to Holyhead Road (the A5).

Two Stoke-on-Trent firms, the Hark Forward Company and the Independent Potter Company, ran day return stagecoach services that stopped to pick up passengers at the Sneyd Arms.

The Hark Forward Company’s coach went to Birmingham via Stone, Stafford and Wolverhampton. The Independent Potter Company’s coach ran to Manchester, Congleton, Macclesfield and Stockport. These two coaches left the Potteries early in the morning and returned late at night.

Stagecoaches were pulled by teams of four or six horses and could travel at a speed of eight to ten miles an hour. Travelling by stagecoach was expensive, and tickets had to be booked in advance. Coaches carried first and second class passengers. First class passengers travelled in the coach, and second class passengers sat on wooden seats on the roof.

The cost of the journey depended on its length. First-class passengers were charged threepence per mile, and second-class passengers were charged one and a half pence per mile.

NSH.2023

Tunstall Was a Prosperous Town

In the 1830s, Tunstall was a prosperous industrial and market town.

There were 17 firms manufacturing pottery. Twelve made earthenware. Three produced earthenware and china. Two manufactured china figures and Egyptian blackware.

The Trent & Mersey Canal ran through the Chatterley Valley. In the valley, there were two brick and tile works. There was a factory making chemicals at Clayhills and a coal wharf on the banks of the canal. Coal and ironstone were mined at Newfield and Clanway.

The east side of Liverpool Road (High Street) from the Highgate Inn to the Old Wheatsheaf Inn had been developed. There were shops on Liverpool Road and in Market Place (Tower Square) where a market was held on Saturdays.

The market opened early in the morning and closed late at night. It was a bustling market with stalls selling a wide range of goods, including household items, furniture, shoes, and clothing. Green grocers sold fruit and vegetables. Farmers’ wives had stalls in the Market Hall, where they sold eggs, butter and cheese. Between the Market Hall and Liverpool Road were stalls selling meat, fish and poultry.

Saturday was the busiest day of the week for shopkeepers and innkeepers. The market attracted customers from Butt Lane, Kidsgrove, Mow Cop, Harriseahead, Packmoor, Biddulph, Chell and Goldenhill.

Copyright David Martin 2023

NSH2023/Revised2025

The Lamb Inn by Henry Wedgwood

An extract from his book Romance of Staffordshire

The Lamb Inn on Liverpool Road (High Street), kept by Nancy Grey, was where Tunstall’s “aristocracy” assembled in the evening to discuss the pottery industry.

The most important issues facing the town were the state of the pottery industry and how well crockery was selling. Everything was alright if things were going well for the industry, and little else could go wrong. The owners of Tunstall’s pottery factories enjoyed sitting around a blazing fire in the Lamb, discussing matters that interested them. They were an exclusive group who did not like strangers from the other pottery towns calling at the inn for a drink. The pottery manufacturers believed these calls were made to spy on their business affairs, steal their patterns, or learn more about their production methods.

“Let every town keep to itself. We want a visit neither from the master nor the men”, was the sentiment of people living in the six towns. Nothing could exceed the jealousy with which the potters looked upon one another. Every town was sure that it possessed some secret that it was not in its interest to let any of the others know. If workmen came to see each other, there would surely be a fight, and arguments developed when men from other towns visited the Lamb.

One night, Jimmy Caton, landlord of the Duke of Bridgewater Inn, Longport, called at the Lamb.

Caton was fond of boasting about how much money he had made and about his possessions. Pottery manufacturer Benjamin Adams was in the Lamb. He was talking about the money he was making and his hunters – his favourite breed of horses. Caton, who had been ignored because he was a stranger, could not bear to hear anyone talk about wealth without taking part in the conversation. Burslemites believed that Caton possessed as much money as a strong man could carry. Thinking himself as good a man as any, Caton made disparaging remarks about Adams’ hunters. Adams did not like Caton’s comments, and they started arguing.

Adams said that he had enough money to buy and sell Caton, who replied by saying that he was worth as much money as any man in Tunstall. After boasting about their wealth, the two men began discussing their physical powers, and Adams offered to fight Caton. He accepted the challenge. The two men stripped to the waist and fought like common labourers in the yard at the back of the inn.

(Edited by North Staffordshire Heritage. Unfortunately, Wedgwood does not tell us who won the fight.)

The Old Swan Inn, Hanley

In his Romance of Staffordshire (Published in the 1870s), Henry Wedgwood describes the Swan Inn, a coaching inn where stagecoaches to London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool stopped to pick up passengers. He writes:

It is wonderful how soon public buildings pass from memory. How completely the “Old Swan Inn”, Hanley, is now buried in the past and, along with the memory of those who met to socialise under its roof.

The old inn was a large building with strange-looking wings and gable ends, with square-built chimneys and gothic windows, some of them exceedingly small and mullioned by heavy stonework. There were iron palisades at the front of the inn and an extensive bowling green at the rear. The front entrance was covered by a flat canopy supported by stone pillars.

Inside there were queer, old, little rooms with chimney nooks and ancient screens that told of bygone days. There was one large room used by local clubs and for civic celebrations where speeches were made about the state of the pottery industry.

One of the rooms at the rear of the inn had a large bay window that overlooked the bowling green. In this room, the magistrates held petty sessions to try summary offences. They sent those suspected of committing indictable offences for trial at Quarter Sessions or the Assize Courts, which sat in the Shire Hall at Stafford.

(Edited by North Staffordshire Heritage)

Bull Baiting in 18th Century Hanley

Hanley’s bullring, where bulls were baited on Sundays, was near the Cock Inn at Far Green. Henry Wedgwood, in his Romance of Staffordshire, says the bullring was a place where ” some poor animal was attacked by dogs” and tortured by men. He writes:

Bull baiting was organised by men who frequented the Cock Inn, a small tavern with a thatched roof.

Writing about bull baiting, Wedgwood asks his readers to picture an infuriated bull made fast to a stake or a ring driven into the ground. The bullring was surrounded by hundreds of people – both men and women. Standing in front of the crowd were men restraining snarling dogs struggling to break free and attack the bull.

Spectators were betting on which dog would bring the bull to its knees. There were excited shrieks from its supporters when the dog they had bet on was sent into the ring. They cheered if the dog’s teeth tore flesh from the bull’s nose or another part of its body.

During the winter months, when bull baiting took place in the late afternoon or early evening, the ring was lit by torches made from long pieces of pit rope resoaked in pitch.

According to Wedgwood, the crowd surrounding the bullring was a drunken rabble that included colliers whose faces were as black as midnight and potters wearing leather aprons and breaches.

When the bull collapsed with exhaustion, its tormentors, egged on by the spectators, attempted to force it to get up by prodding it with sharp spikes or pouring hot tar onto the most tender parts of its body.