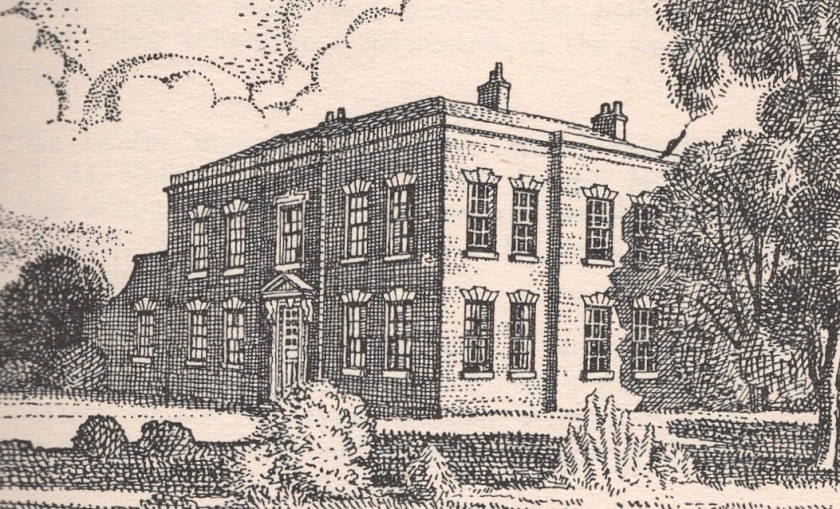

Surrounded by woods and parkland, Stallington Hall, near Blythe Bridge, was a country house that became a mental hospital.

Stallington Hall was a Queen Anne-style mansion built in the 18th century. It was the home of landowner Richard Clarke Hill. His daughter, Sarah, married Smith Child, who lived at Newfield Hall in Tunstall. The couple were married at St Nicholas’ Church, Fulford, in 1835. They lived at Newfield Hall until 1841, when they moved to Rownall Hall, Wetley.

In 1853, Richard Clarke Hill died, and Smith Child and his family went to live at Stallington Hall.

Smith Child, who was a magistrate, became a Member of Parliament. He became a baronet in 1868. His full title was Sir Smith Child, Baronet of Newfield and of Stallington in the County of Stafford, and of Dunlosset (Dunlossat), Islay, in the County of Argyll.

Sir Smith Child died at Stallington Hall on 27th March 1896. His grandson, Sir Smith Hill Child, inherited the estate.

Sir Smith Hill Child was educated at Eton and Christ Church College. He became a professional soldier and fought in the Boer War. In 1910, he became the commanding officer of the 2nd North Midland Brigade (Royal Field Artillery.

On 3 August 1914, Germany declared war on France. German troops invaded Belgium, a country Britain had promised to defend against German aggression. On 4 August, Britain declared war on Germany. The First World War had begun, and the brigade was sent to France. where it fought at Loos and on the Somme.

Sir Smith Hill Child was mentioned three times in dispatches. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George. Promoted to Brigadier General, he was given command of the Royal Artillery’s 46th Division. On 29 September 1918, the Division crossed the St Quentin Canal and broke through the Hindenburg Line, taking 4,000 prisoners. The French Government awarded him the Croix de Guerre.

When he returned home, Sir Smith Hill Child stood for Parliament. His election campaign was successful, and he represented Stone from 1918 to 1922. In 1925, he married Barbara Villiers. Shortly after their marriage, they left Stallington Hall. The couple had two daughters, Teresa and Mary.

The hall and its grounds were sold to the City of Stoke-on-Trent, which converted it into a mental hospital.

The conversion cost £20,000. Lady Aspinall opened the hospital on 18 September 1930. Miss M. A. Cahill was the matron. The hospital accommodated 81 patients and possessed an operating theatre and a dental surgery.