During the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution changed the face of Britain, making it the ‘workshop of the world’.

Earthenware factories were built in Tunstall, a township that included Sandyford, Newfield and Furlong. At the end of the 18th century, there were seven factories making pottery. Small coal and ironstone mines were scattered throughout the district. Blue bricks and tiles were produced in the Chatterley Valley.

As early as 1735, William Simpson was making earthenware in the township. By 1750, Enoch Booth had a factory near a field called Stony Croft. The factory made cream coloured ware glazed with a mixture of lead ore and ground flint.

In 1763, Admiral Smith Child built Newfield Pottery, where he produced earthenware. By the 1780s, two brothers, Samuel and Thomas Cartlich, were making pottery and mining coal at Sandyford. There were brick kilns, coal mines, a flint mill and a crate maker’s workshop at Furlong.

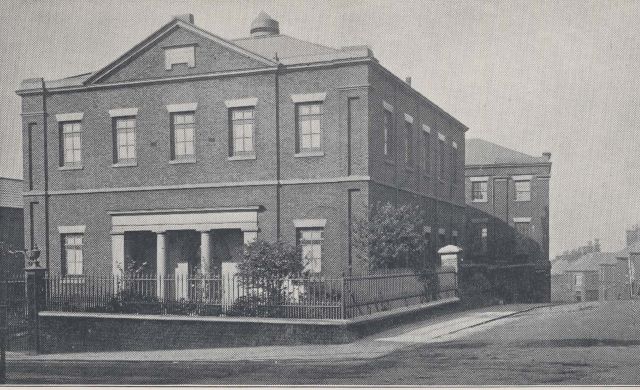

During the 1740s, George Booth and his son Thomas, leased a pottery factory on an estate called Will Flats adjacent to Furlong Lane. In 1779, Burslem pottery manufacturer William Adams rented the factory and part of the estate. On 1 March 1784, William bought the factory and the land he was renting. He changed the estate’s name from Will Flats to Greengates. The old factory was demolished, and William built, Greengates, a new factory on the site where he made high quality stoneware and jasper ornaments for the luxury market.

William employed a Swiss modeller, Joseph Mongolot, to help him create the models from which the moulds used to produce the bas-reliefs for jasper and stoneware were made.

Pottery produced by William was sold to wealthy customers. They purchased ware from his showrooms in Fleet Street, London or visited the Greengates factory to buy tea sets, dinner services, jasper, and stoneware ornaments.

The 6th edition of William Chaffer’s book ‘Marks and Monograms on Pottery and Porcelain’ tells us that some of the jasper made at Greengates was ‘equal, if not superior, to anything made [by Wedgwood] at Etruria.’